Venture valuations have fallen off a cliff, but they are still too high.

Valuations rise and fall with the volume of dollars invested in startups according to a stable ratio: for every one percent change in funding, valuations move two-thirds of a percent.

But since peaking in late 2021, valuations have only fallen 0.4% for every 1% drop in funding. This pricing "error" has accumulated: today's valuations are 60% higher than you’d expect for the amount of capital invested.

In other words, the "shadow price" of venture capital is a lot lower than what we're seeing in announced transactions these days. Never before have valuations and funding diverged so meaningfully from their long-run equilibrium, for so long.

What does it all mean?

Receive my new long-form essays

Thoughtful analysis of the business and economics of tech

A 3-for-2 special

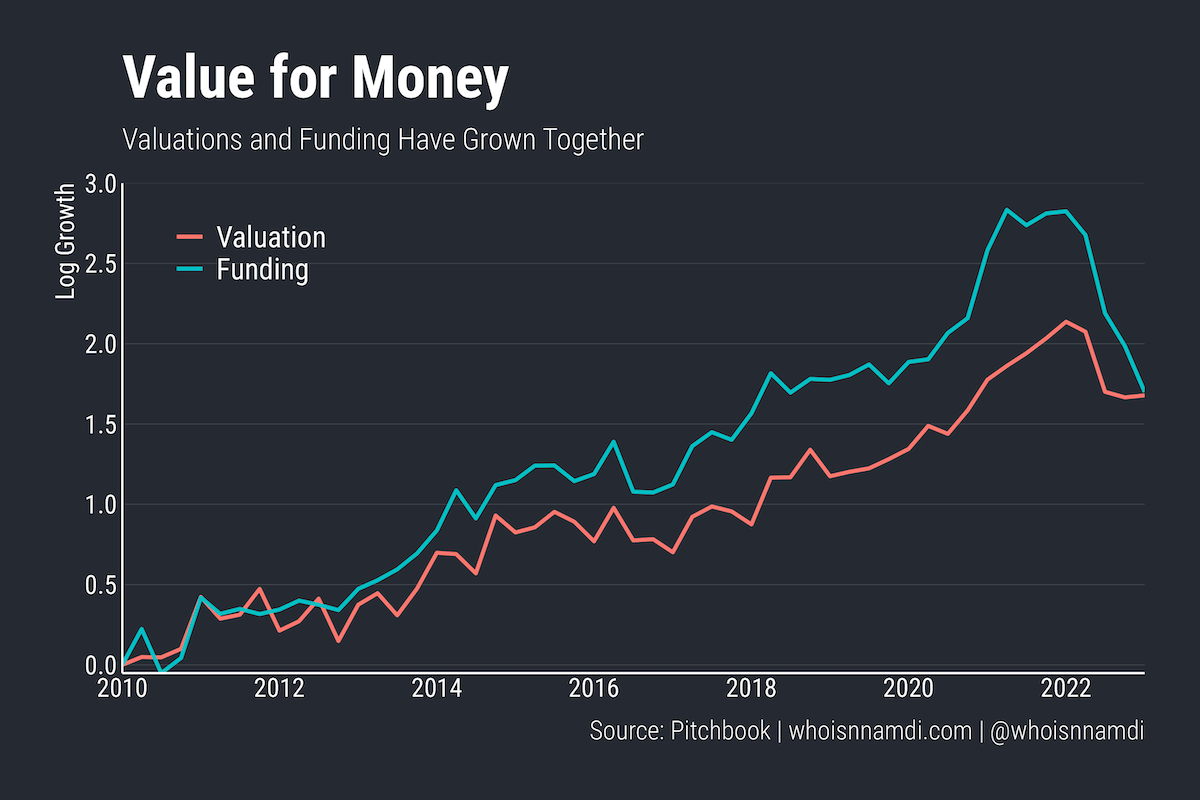

Valuations and capital invested in venture have both grown substantially since 2010:

Interestingly, they trend together. As one rises, the other does too. Same in the other direction.

It's not a perfect relationship, but there's clearly something tying them together.

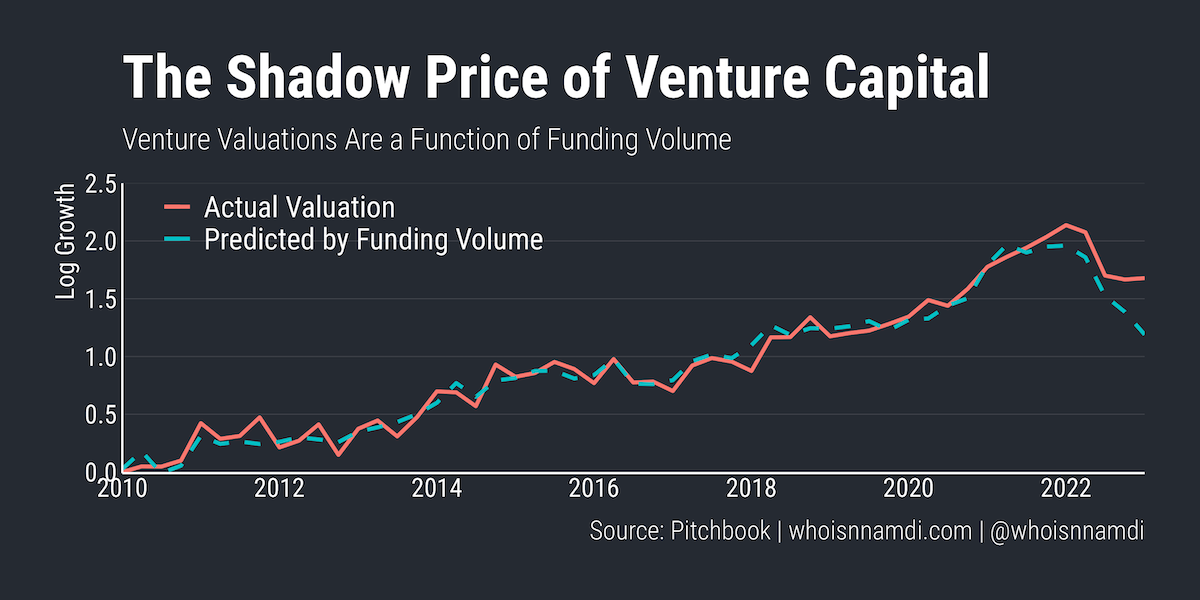

In fact, you can predict average valuations from the capital invested each quarter. The below chart plots actual valuations over time against what we'd predict based on capital deployment – a simple regression of valuations on funding:

Capital invested predicts the average valuation of deals done each quarter.

Most of the time, the "errors" of this capital-based prediction are small. Further, these deviations typically correct themselves within a quarter or two.

In this sense, venture valuations are a function of capital flows. More capital drives valuations ever higher, in a fairly predictable fashion. There's an equilibrium, a balance between the two.

They don't grow at the same rate, however. For every 1% increase in funding, valuations rise about 0.66% or two-thirds of a percent. If you like clean whole numbers, the ratio is about 3:2.

Most of the increased funding goes to rising prices rather than more individual investments. This mirrors points I've made previously:

"the valuation inflation we've seen "comes from" the incredible growth in demand and lack of supply of startup equity"

…

"Additional capital drives opportunistic company formation at the Seed stage. However, the additional capital doesn't improve survival to the later stages – it simply drives prices up for the remaining companies" – It's Valuations (Almost) All the Way Down

Price check, please?

Economists have a term I think is relevant – shadow price – or, the price of something that either isn't typically traded in the market or for which accurate pricing is hard to come by. For example:

- The price of an illicit good (drugs, contraband of various sorts, etc)

- In certain economies like Argentina, the shadow or "black market" price for exchanging the local currency for a foreign currency like the U.S. dollar, which differs from the "official" rate.

Why is this relevant to venture capital?

Well, because so many venture transactions don't happen. Most startups fundraise only once in a while. Founders delay fundraising if they can't fetch an attractive price from investors. Down rounds are verboten. Those deals are missing from the quarterly venture activity data:

- Accounting for these phantom fundraises would lower the average venture valuation, since low prices are the whole reason those deals aren't happening. In other words, there's massive selection bias.

- Companies also tend to be more public about their valuations the higher they are. Journalists love reporting on high valuations. As a result, the data we have on valuations is also likely skewed too high due to reporting bias.

The prices we see investments getting done at are misleading. Thus, the concept of a shadow price applies to venture – it's the price that would prevail if companies were forced to transact at current prices and we had perfect data on all fundraises.

I think of the dashed line in the chart above as something akin to the "shadow valuation" of venture capital investment.

Wow, that's a high price!

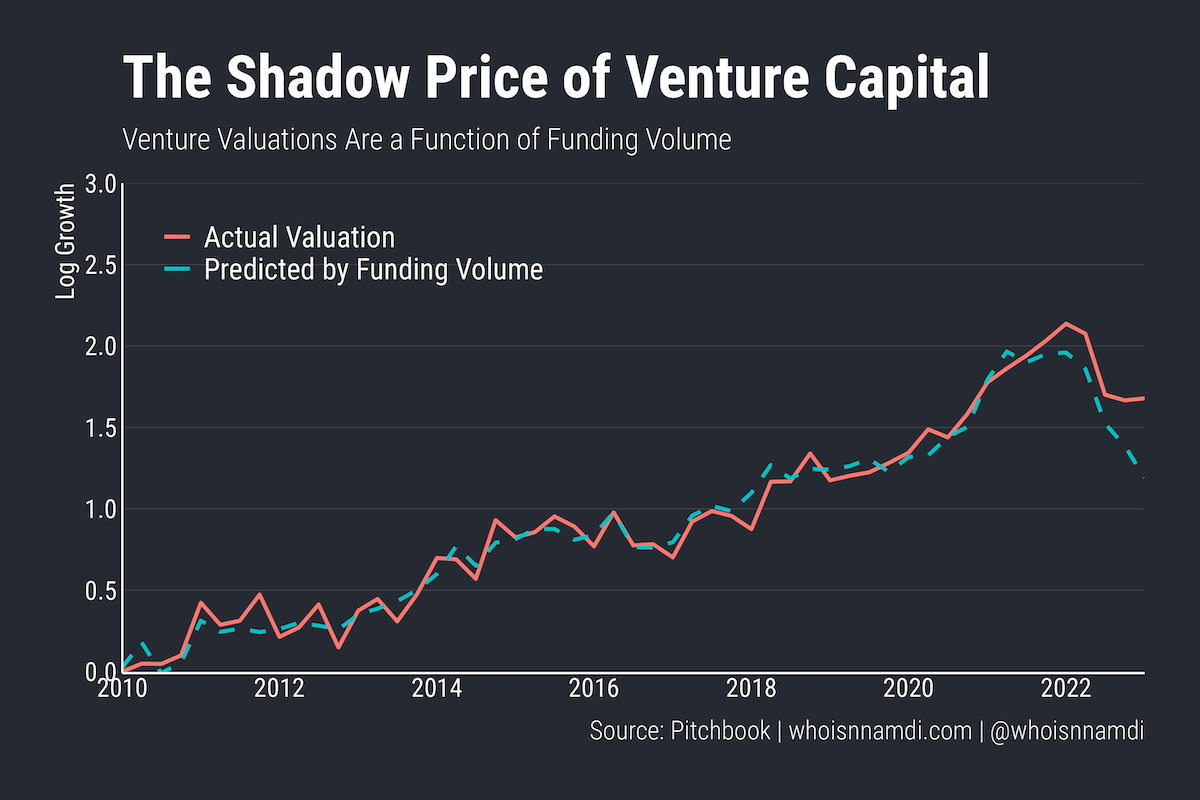

The reliable relationship between prices and funding has broken down in recent quarters.

While valuations and funding have both declined since late 2021, funding declined by much more. Valuations have not fallen by nearly as much as the 3:2 ratio would imply. Instead, since the market peaked the ratio has been more like 5:2, or, said differently, valuations have only fallen 0.4% for every 1% drop in funding.

In other words, even after collapsing, valuations are still too high relative to their historical relationship with funding.

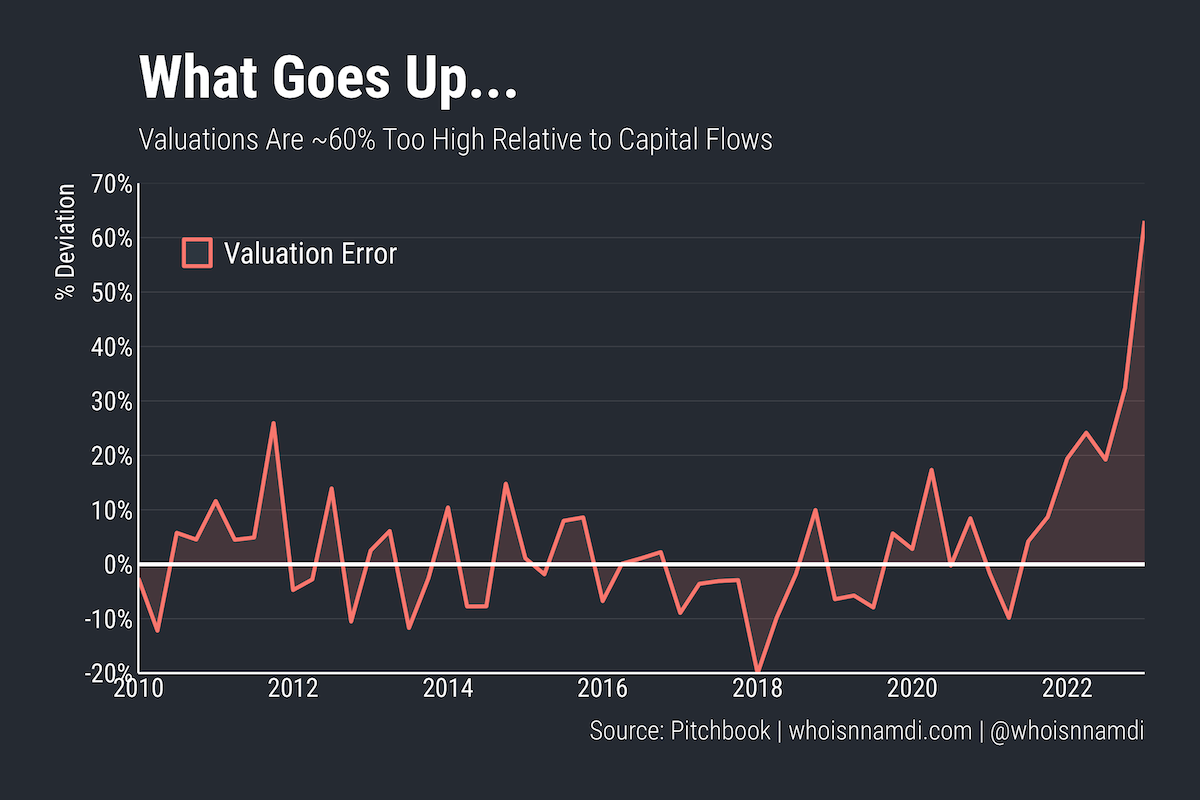

We can visualize this growing "error" – the percentage difference between actual and predicted valuations – shown below. Above the zero line means valuations are too high, below means valuations are too low:

Current valuations are ~60% too high relative to the volume of capital being deployed. There just aren't enough dollars sloshing around to support these prices, at least based on the 10 years of venture history prior to the go-go days of 2021.

Since 2010 valuations have rarely been "off" by more than 20%. 60% is unprecedented.

Again, notice how in the past any deviation from equilibrium quickly reverts, nearly always within a quarter or two. Something has changed – "error correction" is totally absent in recent quarters.

This is worrying. Never in the last decade-plus of venture activity have valuations and funding flows diverged so meaningfully from their long-run equilibrium, for so long. Could this mean there's a lot more pain ahead?

These deals won't last

Now, it's totally possible we have it all backwards.

Till now I've taken for granted the idea that capital flows drive valuations.

Perhaps valuations have risen for separate, independent reasons and funding volume grew to meet these new prices. Thus, it could be funding that corrects itself, rather than valuations. Perhaps the current gap signals funding is too low rather than warning valuations are too high.

Let's check what happened in the past. That is, how have valuations and funding historically reacted to past deviations from their long-run ratio? That would be a strong clue as to which is the driver and which is the passenger here.

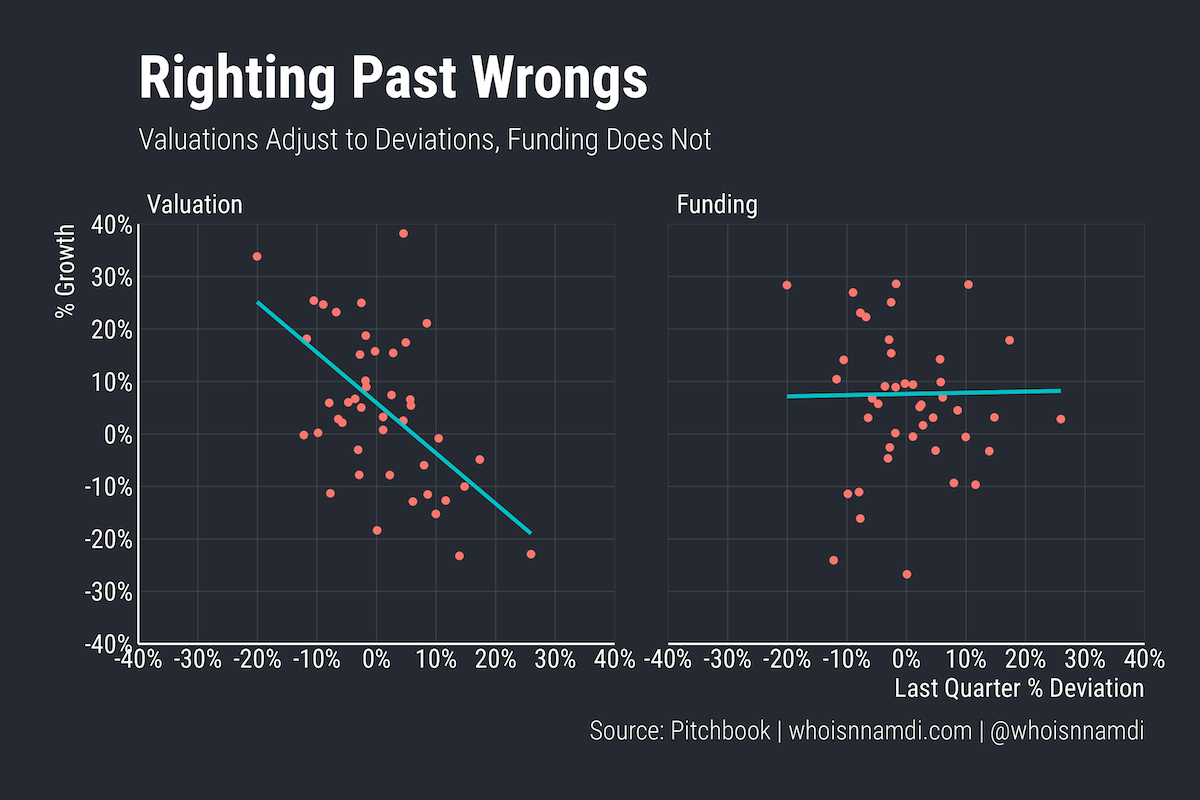

That's straightforward enough – just run a regression of valuation and funding growth on deviations. If valuations react more, then we know valuations correct for past deviations from equilibrium. If invested capital reacts more, then its funding that corrects.

Turns out, valuations correct past deviations (left chart), funding does not (right chart):

When valuations and funding volume drift apart, it's valuations that come running back:

- If valuations are high relative to funding, valuations tend to fall the following quarter

- If valuations are too low relative to funding, valuations rise next quarter

Funding doesn't respond at all.

Deviations reflect unusual valuations rather than abnormal funding. Valuations are out of whack, not funding volume.

Pricing "errors" forecast future valuations, since valuations reliably and quickly respond to those deviations in later periods. The implication? Valuations should fall dramatically from here. That they haven't yet can be chalked up to a combination of market inefficiency and reluctance.

Just like in a Keynesian model of the economy, where sticky, slow to adjust prices exacerbate economic downturns, "sticky valuations" lengthen and worsen venture recessions. Deals that could get done at more reasonable valuations don't happen, as founders and existing investors don't want to take the hit:

Private valuations lag public valuations, often by a substantial amount and for a long time – Old Valuations Die Hard

We should prefer swift, definitive corrections over slow moving train wrecks. Instead, we drag things out. Everyone suffers as a result.

Tourist prices

That venture prices are tied so strongly to capital flows is striking:

- This contradicts standard corporate finance which values companies based on fundamentals. The amount of capital in the market shouldn't impact valuations if the intrinsic value hasn't changed.

- However, that's not what we see – there doesn't seem to be anything "fundamental" anchoring the price of startups. Startups are priced based on the amount of capital in the private markets at the time.

More capital, higher prices. Again, it's not one-for-one, but it's clear most of the capital goes toward higher prices rather than more deals getting done.

In my last essay, I was struck by how sensitive private valuations were to interest rates:

… seven quarters out valuations are up ~25%, falling back to their original level after three years – Don't Discount Interest Rates

As readers pointed out, a pure discounted cash flow (DCF) analysis would never suggest such a large impact. This is a fair point, and one I too pondered.

However, these magnitudes make much more sense in the context of capital flows. Low interest rates attract capital to risky assets like venture capital as investors reach for yield unavailable elsewhere. If capital flowing into startups raises prices, then we really have two simultaneous effects:

- The first is traditional, static, corporate finance, which says interest rates (or rather, the discount rate) influence valuations.

- The second is the dynamic effect of interest rates on venture capital funding, which then impacts valuations via the 3:2 relationship I studied above.

This double whammy is how you end up with such severe valuation swings.

Ironically, it's the tourists who "price" venture investments on the margin – those much-derided investors who, like birds, cyclically flock to and flee from venture investing with the changing economic winds. Us "locals" have no choice but to live with it.

Receive my new long-form essays

Thoughtful analysis of the business and economics of tech