TL;DR: I invest in productivity-enhancing tools for software developers and other technical knowledge workers. If you’re building something along these lines, ping me at nnamdi@lsvp.com

I’ve been obsessed with developer productivity for a long time.

As developments within software tooling, application infrastructure, and data science over the last decade have vindicated my quixotic enthusiasm, I thought I’d finally articulate my rationale in writing.

Manifestos should have mission statements. I’ve always loved Stripe’s:

Our mission is to increase the GDP (gross domestic product) of the internet

They say great artists steal. My artistic design skills are, frankly, terrible (especially relative to Stripe’s), but I’ll steal some inspiration anyway and lay out my mission as follows:

My mission is to increase total software output

Developer productivity is the best way to achieve this. This essay explains why.

The Developer Productivity Manifesto has three parts, this is part 1:

- Part 1: The Developer Productivity Flywheel (you are here)

- Part 2: More (Developers) Isn’t Always More

- Part 3: Leaving Software on the Table

Receive my next long-form post

Thoughtful analysis of the business and economics of tech

Every company is becoming a software factory

It’s been said before, and it’s worth repeating: every company is becoming a software company.

Like Henry Ford’s assembly line 100 years ago, which revolutionized mass production of physical goods, innovation in the production of complex, intricate software products and services promise to transform modern software development.

The Software Revolution is the new Industrial Revolution.

Agile, scrum, waterfall etc. — the various paradigms analogize the factory assembly line and modify it for the modern context. They pose the provocative question, “What can the world of bits learn from the world of atoms?”

In this light, I modify the above: every company is becoming a software factory.

But analogies to old-school industry only take us so far.

In the factories of old, labor was poorly-skilled, poorly educated, poorly treated, and poorly compensated. Today, as before, labor remains the key input to production. However, in the modern software factory, labor (i.e. software developers) is highly-skilled, well-educated, well-treated (at least in more progressive companies), and mostly importantly, well-paid.

My goal as an investor and citizen of Silicon Valley is to increase total software output. Maximizing the software output requires understanding what I call, the software production function — how we map from inputs to outputs in software development. The exact function is likely unknowable, but we know for sure developers are the key input. Therefore, let’s start with this simple mapping:

Basic enough, but we can do better. Economists often decompose variables into the extensive (“how much input” / “how many software developers”) and intensive (“how much per input” / “how productive”) margins:

So, we can grow software output in two ways: more developers or higher developer productivity.

Why we should care about developer productivity

“While many people posit that lack of developers is the primary problem, this study… found that businesses need to better leverage their existing software engineering talent if they want to move faster, build new products, and tap into new and emerging trends” — The Developer Coefficient 2018, Stripe

Software developers are the scarce, precious resource of software development — extremely expensive to obtain, train, and retain. Anything that makes software developers more productive will itself be highly valuable.

However, productivity in software development tends to decline over time rather than increase.

This is a counterintuitive claim, so let’s unpack it.

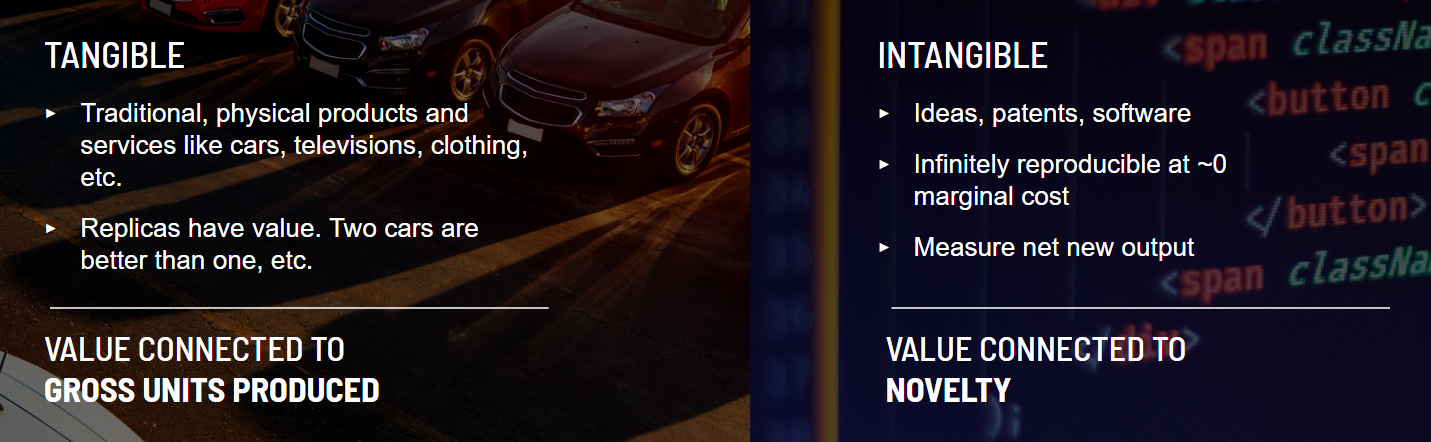

First, it helps to delineate two different types of production — the production of tangible and intangible goods:

Tangible goods include traditional, physical products and services like cars, televisions, clothing, etc. Importantly, due to their tangibility, replicas have value. Two cars are better than one, and so on. It therefore makes sense to talk about gross “units” of production — cars assembled, televisions manufactured, etc.

On the other hand, intangible goods constitute non-physical products like ideas, patents, and… software. Intangibles are infinitely reproducible at nearly zero marginal cost. As such, it doesn’t make sense to measure intangible output in terms of gross “units’’ of output. Rather, only net new output matters.

Software is one such intangible. Copying existing code is as easy as running git clone on a repository. This alone does not generate incremental value — the value was in writing the original code.

With intangibles, novelty is what matters: new ideas, new designs, and new software. There’s a reason you can’t patent something already patented — there’d be no value in doing so. Similarly, new code moves the ball forward.

Let’s edit our previous equation to emphasize novelty:

It turns out, this trivial change makes a huge difference.

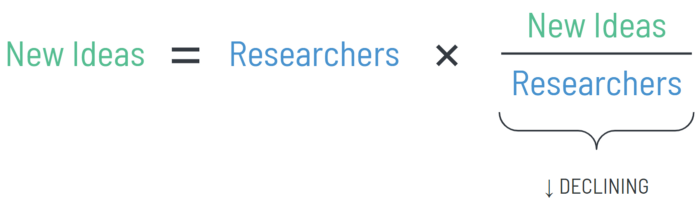

Why? Economic evidence suggests that, unlike physical goods, idea productivity tends to decline over time. The intensive margin of the “idea production function”, i.e. the number of new ideas generated by a given number of researchers, falls dramatically as a field progresses:

Don’t believe me? Here’s one example that should resonate with fellow technologists: Moore’s Law.

Are ideas getting harder to find?

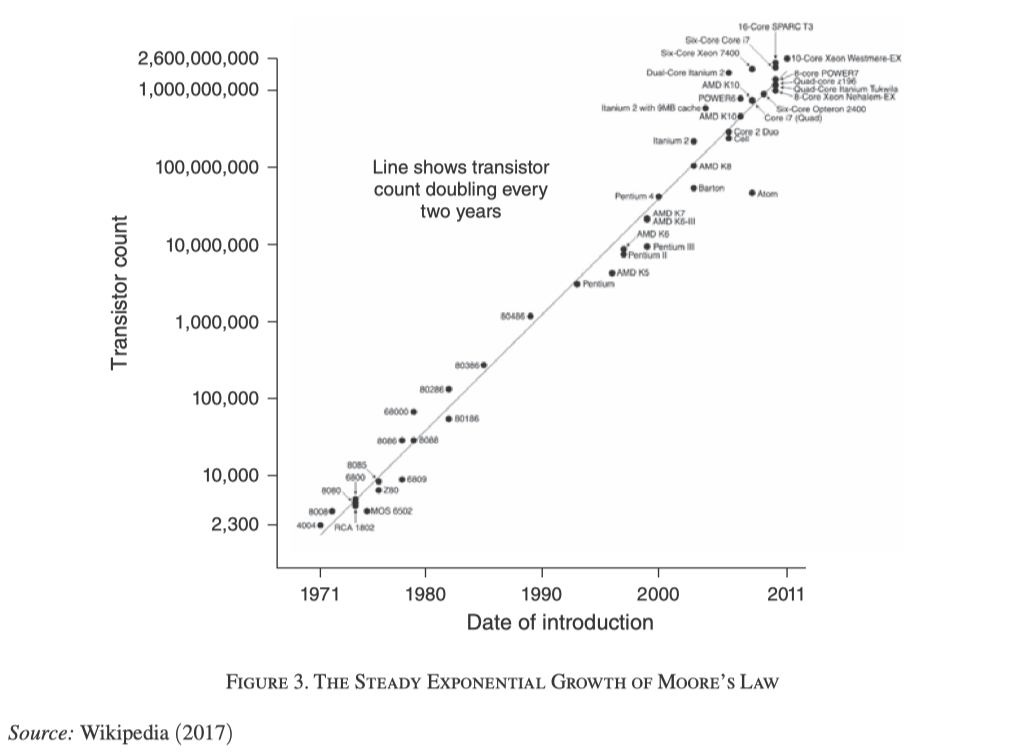

Moore’s Law describes how manufacturers cram twice as many transistors onto computer chips every two years.

Sustaining this self-fulling prophecy of “2X every 2 years” requires massive research teams to churn out new ideas and insights around chip design and manufacturing. It’s clear from the data that Moore’s Law is not some a priori law of the universe, but rather a goal set by chip manufacturers and researchers:

“Many commentators note that Moore’s Law is not a law of nature but instead results from intense research effort: doubling the transistor density is often viewed as a goal or target for research programs.” — Are Ideas Getting Harder to Find?

Transistors are tangible, but the ability or know-how to condense their size over time is an idea and, therefore, intangible. Intellectually, we should separate the physical production of literal computer chips from the ideas that enable this feat.

As it turns out, the old ideas just won’t do — what got you here won’t get you there.

In a fascinating and landmark paper, Stanford and MIT economists Nicholas Bloom, Charles Jones (hey professor!), John Van Reenan, and Michael Webb frame the constant growth in the density of transistors as evidence of a constant flow of new ideas and innovations:

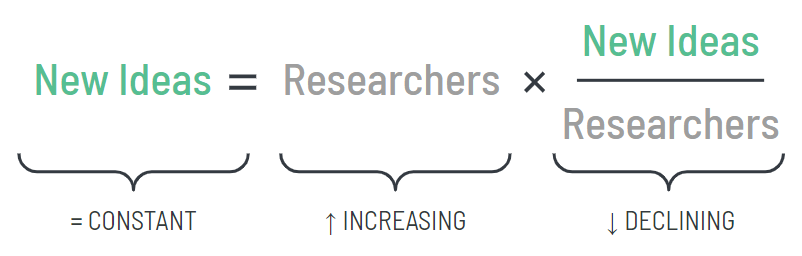

If idea output is constant, growth in the number of researchers implies shrinking research productivity. If the flow of new ideas in semiconductor manufacturing is constant (as evidenced by Moore’s Law roughly holding steady) and the number of chip researchers increases over time, then we know (via simple arithmetic) research or idea productivity must decline:

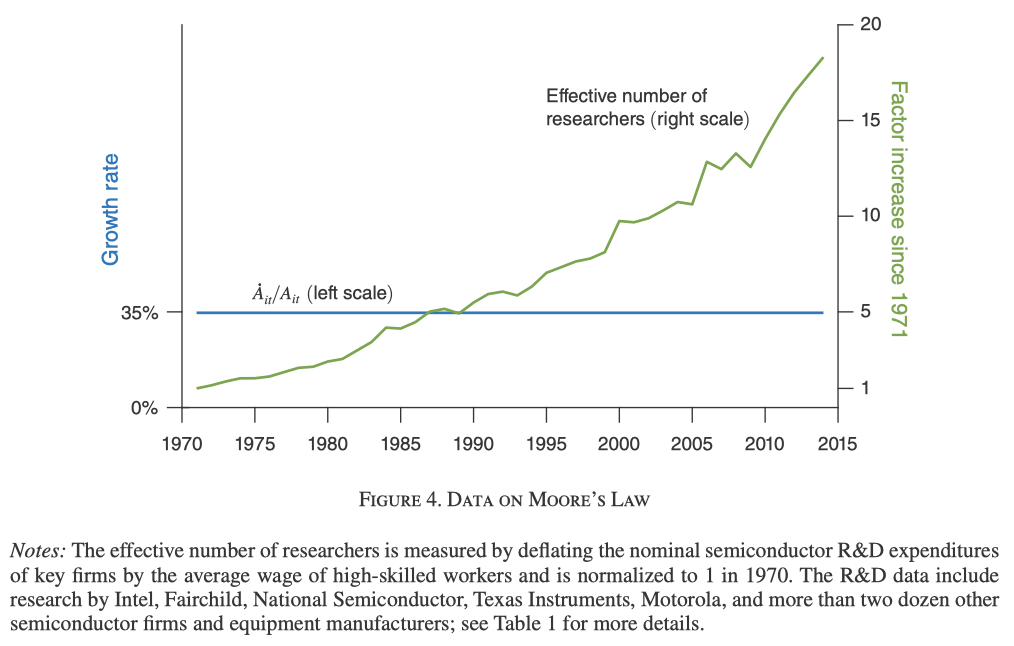

And that’s exactly what we see. Generating constant growth in the number of transistors on a chip has required many more semiconductor researchers and scientists over time, about 18 times as many in 2014 relative to 1971:

Measured in terms of transistor density gains, research productivity has declined 18X over a 45-year period, which is to say it’s about 5% of what it used to be, a dramatic, precipitous decline in idea productivity. And as presented in the paper, the same phenomenon holds true in many sectors, such as agricultural and medical research.

The evidence is clear: new ideas are hard to find and only getting harder. Analogously, if we assume new software represents new ideas, it only follows that new software is increasingly difficult to create too.

The work of software developers is analogous to semiconductor R&D. Engineering teams are tiny idea factories, and new ideas get harder to produce over time.

This is why developer productivity falls over time. The ability of software developers to write novel applications tends to decline over time, as happens in almost any idea-centric production process. When so much code has already been written, it’s difficult to improve upon the status quo.

The developer productivity flywheel

Breaking away from this gravitational, productivity-sucking force field won’t be easy. However, we can reach escape velocity by aggressively enhancing developer productivity rather than watching it deteriorate.

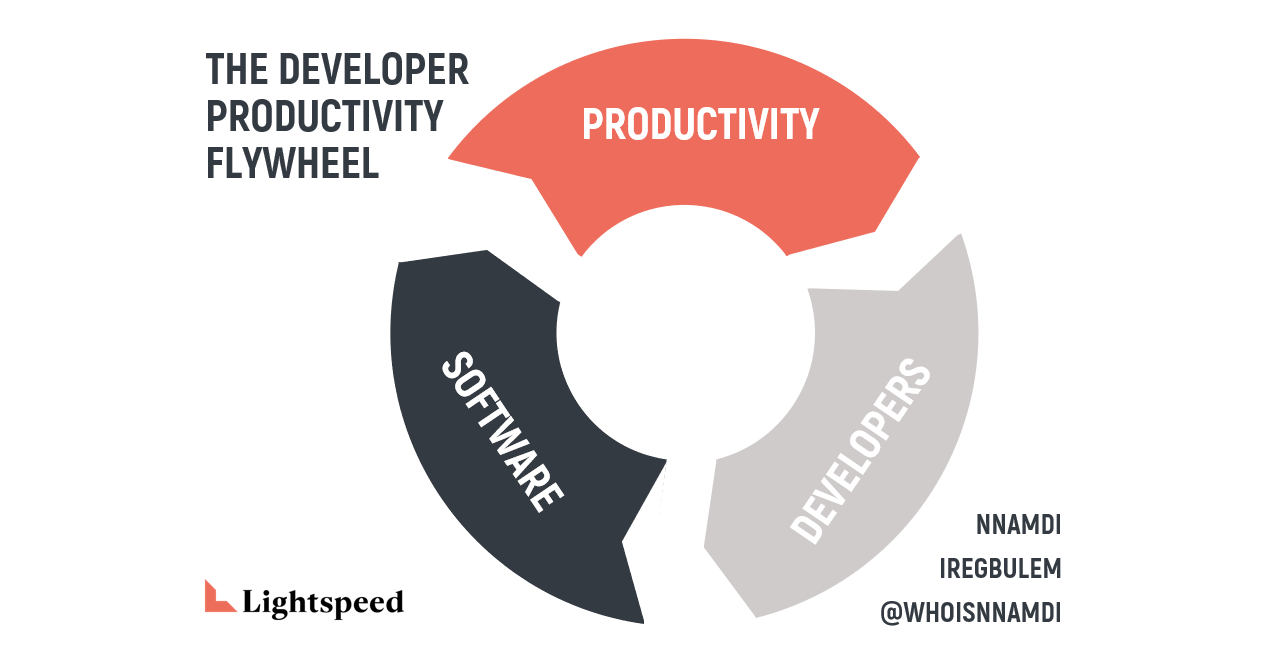

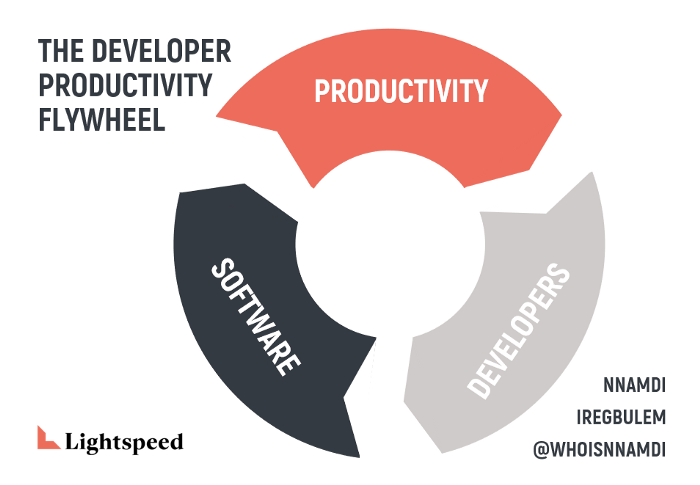

Flywheels help technology startups achieve velocity, and software development is no exception. Since no mention of flywheels in a technology essay is complete without a visualized loop, here it is:

To explain:

- New developer productivity tools make software developers more productive.

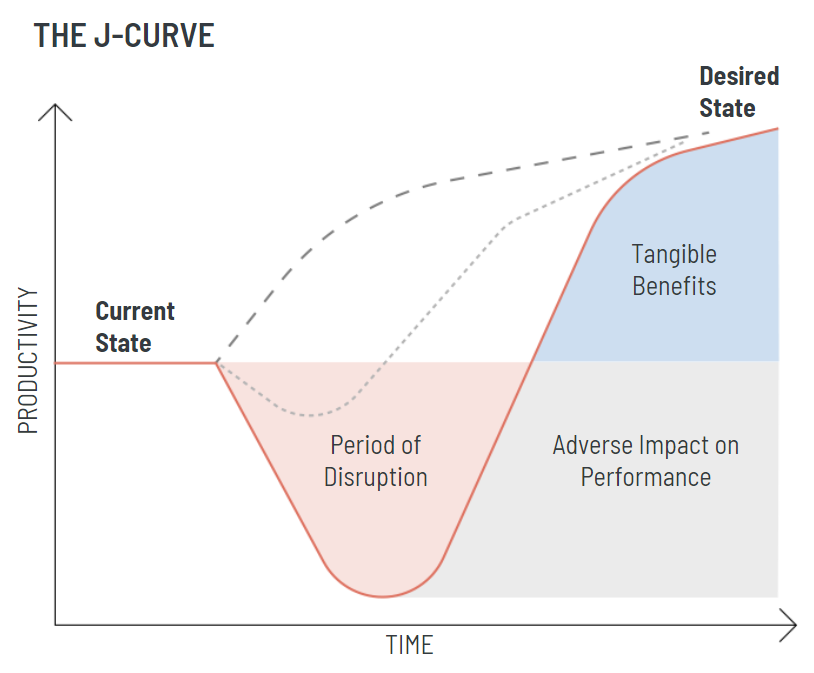

Simple enough, though we shouldn’t be so naive as to think it always works out so cleanly. New tools initially impair developer productivity, as individual contributors and teams adjust to new software, interfaces, and workflows. Complex tooling can drive productivity through the ground if recklessly implemented.

This dynamic generates the familiar “J-Curve” of initially declining productivity before tangible benefits are eventually realized:

So I should be precise — new productivity tools thoughtfully applied make developers more productive. That productivity may not immediately materialize, either because it’s difficult to measure (Commits? Lines of code? Shipped releases?) or because adjustment takes time. This only reinforces the importance of investing sooner, as to frontload the trough.

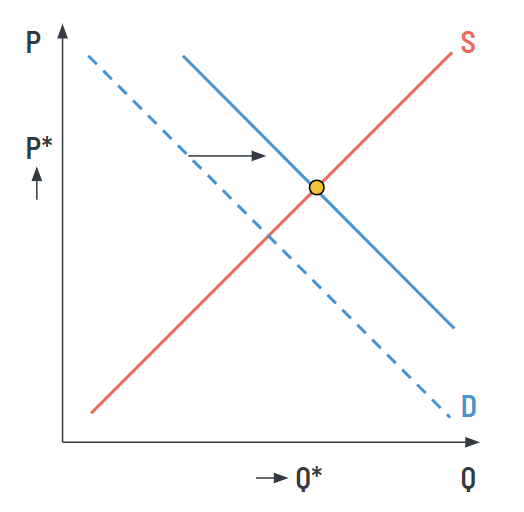

2. Higher developer productivity drives companies to hire more software engineers.

Remember your supply and demand curves from economics 101? Higher productivity pushes out the developer demand curve. Companies take advantage of enhanced productivity by hiring more developers and paying them more too:

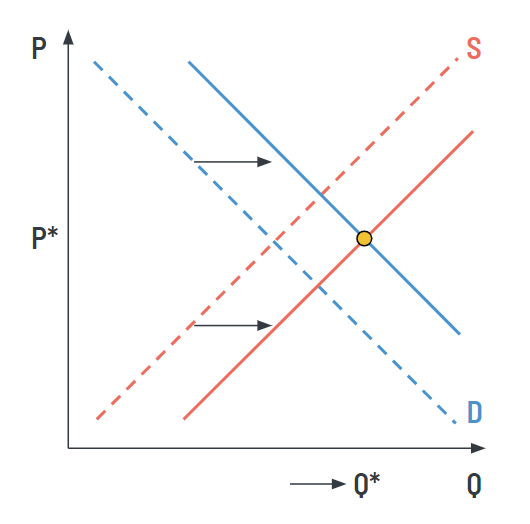

In some cases, the enhanced productivity not only makes existing developers more productive but lowers the bar enough that others can now become software developers too. This pushes out the the developer supply curve, increasing employment further:

3. More developers working at higher productivity levels ship more software, a subset of which is itself developer productivity tooling.

As previously discussed, if we simply increase the number of developers without maintaining productivity, we merely tread water. What’s crucial here is that developer productivity and employment rise together. If they do, we get more software output, and that new software will itself drive higher productivity.

4. Loop

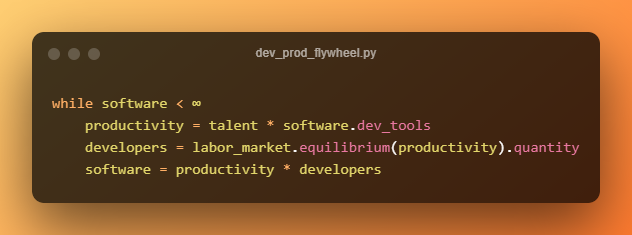

For the technically inclined, here’s how the logic goes in code form (much more compact 😅):

In other words:

This is what I like to call, the developer productivity flywheel.

The future of productive, economical software development rests on running this flywheel as quickly as possible, iteratively looping through virtuous cycles of productivity, employment, and software output growth.

However, there is “no silver bullet.” There isn’t “one weird trick” to massively supercharge developer productivity.

Instead, we must attack the problem from every available angle if we are to succeed.

Ready for more? Here's Part 2.

Follow me on Twitter, subscribe to my monthly essays here, and reach out to me directly via nnamdi@lsvp.com